The Superstar Composer of Mozart’s Time (It Wasn’t Mozart)

In terms of landing a great job, Mozart could do nothing right. And Giovanni Paisiello was the man who could do no wrong. From Naples to Russia to Vienna to Paris, Paisiello (1740-1816) dominated the international opera scene, winning favor and commissions from monarchs and emperors. Popular in his native Naples, he was the darling of Catherine II of Russia, as well as Napoleon himself.

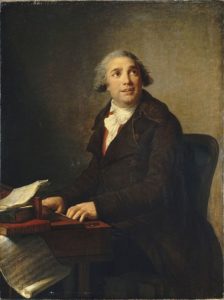

Operatic superstar Giovanni Paisiello

Born in the coastal Italian city of Taranto, Paisiello’s singing talents landed him at the Conservatorio di S Onofrio in Naples at age 14. Naples became his professional base for much of his career. His first operas were staged in 1764 in Bologna and Modena; by 1766 he established himself in Naples as a freelance composer of operas both serious and comic. By May 1768, King Ferdinand IV of Naples had taken a liking to Paisiello’s music.

Then there is the curious matter of Paisiello’s marriage, which took place on September 15, 1768. “Took place” is not very accurate; in reality, it was “solemnized” against Paisiello’s will while he was in prison. Paisiello had entered into a marriage contract with a widow named Cecelia Pallini. Then he apparently had second thoughts. He tried every excuse and legal channel to get out of the contract, but Pallini successfully sued him for matrimony, putting Paisiello behind bars until the marriage was finalized by the courts. Not the healthiest start to a relationship. But Paisiello found his marriage useful a little bit later in his career; more on that shortly.

In the 1770s, Paisiello’s career took off. He completed 25 operas in 1770-1775 for a variety of theatres in Naples, Turin, Modena, Milan, Rome, and Venice. From 1774 he received recognition and commissions from the Neapolitan court. His Il duello (1774) was recast in French as Le duel comique in Bourgogne in 1776.

That’s when Catherine II of Russia got involved, offering Paisiello a lucrative salary (3000 rubles per year) to serve as her maestro di cappella in St. Petersburg. Starting in 1776, Paisiello composed operatic works, led the court’s orchestra and opera company, wrote occasional and keyboard works, and taught piano to the noble ladies in Catherine’s court. Catherine II renewed his contract in 1779 with a raise to 4000 rubles per year.

Here’s the funny thing: Catherine II hated opera and remained lukewarm about music in general. She merely kept the opera theater at court for appearances. For this reason, Catherine II decreed that operas could last no longer than 90 minutes.

Catherine II of Russia

Under these circumstances, however, Paisiello flourished, producing over a dozen operas in St. Petersburg in a variety of genres, from comedy to tragedy to dramma giocoso (the in-between tragi-comedy category that also includes Mozart’s Don Giovanni of 1787). Some highlights: La serva padrona (1781), a remake of Giovanni Pergolesi’s early Classical masterpiece; I filosofi immaginari (1779), a buffoonish comedy about a dude pretending to be intelligent to impress his crush’s dad; and The Barber of Seville (1782)—yes, you read that right.

Interesting side note on The Barber of Seville. You’re thinking of Rossini, right? Well, Rossini (1792-1868) was almost 24 years old when his version of The Barber of Seville was premiered in Rome on February 20, 1816—and Paisiello was still alive. (Fun fact: Rossini was a leap-year baby, born on February 29.) Paisiello was still enormously popular and his fans considered Rossini’s Barber remake as an affront to Paisiello’s honor, storming the stage at Rossini’s premiere. As we all know, in the end Rossini’s effort completely obliterated Paisiello’s version. In hindsight, this was nothing more than karma for the composer who had “stolen” La serva padrona from the hapless Pergolesi (who had died at age 26).

Now back to Russia. In 1782, Catherine II renews Paisiello’s contract again, but frankly the dude is starting to get sick of the place. He’s looking for a new gig. He starts sending his latest scores to King Ferdinand IV (Naples) through the diplomatic mail. In November 1783, Barber of Seville is presented at the Neapolitan court. In December 1783, Ferdinand officially offers Paisiello the coveted position of court opera composer in Naples. But Paisiello was still under contract to Catherine II. So what is an international superstar composer to do?

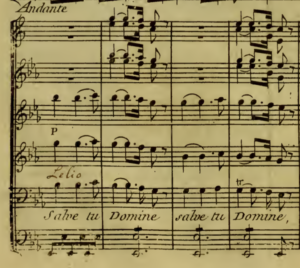

Paisiello’s aria “Salve tu, domine” from his opera I filosofi immaginari

Paisiello invents a story. He tells Catherine II that his wife is very sick and needs some sort of extended treatment… you know, in an unnamed location other than Russia. Hesitant to lose her star composer, Catherine II grants him a year of paid leave. Paisiello departs St. Petersburg with the cash, never intending to return. I guess at this point he was thankful for his disputed marriage, question mark?

Paisiello’s new position in Naples carried no regular schedule or salary, so he took his time getting back to Italy. He spent summer 1784 in Vienna, where he wrote a new opera (Il re Teodoro in Venezia), a “heroic-comic drama,” which had its premiere in the Burgtheater on August 23. This only multiplied his fame. Il re Teodoro was produced in Paris in 1787, opening up a big new market for him–as we shall see shortly.

The clip below, “Salve tu, domine” from Paisiello’s I filosofi immaginari, is an excellent example of his comic style. (This opera is variously titled Gli Astrologi immaginari.)

Mozart adored Paisiello’s music and was transfixed by its comic properties: the pitter-patter text setting, the exaggerated archetypes, the over-the-top melismas, the snappy witticisms, the virtuosic change-on-a-dime interruptions reminiscent of classical cartoon music. In 1782, Mozart composed a set of piano variations on Paisiello’s “Salve tu, domine” from I filosofi immaginari (K. 398). It’s not hard to see why I filosofi immaginari (“The Imaginary Philosophers,” i.e. “Pretend Smart Guys”), an opera about pompous idiots who greet each other pretentiously in Latin, would appeal to Mozart’s irreverent sense of humor.

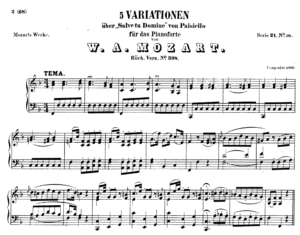

The theme of Mozart’s K. 398, Variations on Paisiello’s “Salve tu, domine”

Charged with comic imagery, Mozart’s Variations K. 398 also contain tender moments, as well as flights of keyboard virtuosity rarely matched even in his more substantial works. K. 398 provides an excellent example of Mozart’s variations form, and perhaps a window into his style of structured improvisation.

It’s not just the comic qualities that made Paisiello’s music so appealing. The Italianate clarity, the neatly structured phrases, the transparent textures with layers of distinct rhythms, its pure insouciance, the endless melodic invention—all of these became crucial to Mozart’s language as well. Paisiello’s 8 piano concertos constitute one of the most significant mid-Classical contributions to the genre, alongside those of Haydn and Johann Christian Bach in London. In this sense, Paisiello paved the way for the Mozart’s late operas and concertos.

In the clip below, during the first movement of Paisiello’s Concerto no. 2 in F Major, the soloist Mariaclara Monetti does something absolutely clever (around 6:39): she borrows a cadenza-like passage from Mozart’s K. 398 to round out her cadenza and usher in the final orchestral tutti (compare to 5:35 in the Mozart K. 398 video above).

But in career terms, Mozart was definitely on the losing side of all this. Paisiello could literally trip down the stairs and end up with a new opera commission or job offer. Mozart was desperate (musically and financially) for operatic commissions. He saw himself first and foremost as a composer of opera. But as Haydn wrote in an 1787 letter, “It enrages me to think that the unparalleled Mozart is not yet engaged by some imperial or royal court!”

Oh but we’re not done. Paisiello saunters casually back into Naples in late 1784, basically saying, “I’m kind of a big deal.” But around 1790 he seems to have suffered a breakdown due to overwork. Turns out, he was receiving too many high-profile opera commissions, both from Ferdinand’s court and from outside theatres. Around this time he transitioned from composing opera to church music, all while in the comfortable employ of the Neapolitan court.

Then things got weird. In 1799, French military forces conquer Naples; Ferdinand and his court flee to Sicily. But Paisiello does not join them. The new French leaders, already well familiar with Paisiello’s work, instantly name him maestro di cappella to the new French republic in Naples. A month later, however, Ferdinand retakes Naples and expels the French army. Paisiello is investigated for treason and suspended, but ultimately pardoned and rehired by Ferdinand’s court in 1801 (“how could I stay mad at you?”).

Ferdinand IV of Naples

This all sounds crazy but in 1806 the same exact thing happened again. The French army, under Napoleon’s brother Joseph, defeats Naples and sends Ferdinand to Sicily for a second time. One of Joseph’s first actions is to place Paisiello in charge of all the court music (opera, church, chamber music). Paisiello was awarded the Legion d’Honneur in 1806 and Napoleon granted him a handsome pension in 1808, which was backdated to 1804 (woohoo, suddenly 4 years’ worth of pension!). Much later in May 1815, Ferdinand, never one to give up, defeats the French again and publicly pardons Paisiello again, who held this last Neapolitan post until his death in June 1816.

This all-too-complicated back-and-forth conquest explains why Ferdinand is variously titled Ferdinand IV of Naples, Ferdinand III of Sicily, and Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies. (If you answered “one” to the question “How many Sicilies are there?”, you answered wrong.)

And I skipped over the part where Ferdinand “lent” Paisiello to Paris in 1802-1804, at Napoleon’s personal invitation, to be Napoleon’s court composer of operas, military marches, and church music. By 1804, newspaper reports surfaced in Paris that (again) Paisiello tired of his glamorous appointed position. He stuck around Paris just long enough to compose a new mass setting for Napolean’s imperial coronation at Notre Dame Cathedral on December 2, 1804. He did the gig and then returned home.

Ferdinand and Napoleon, enemies on the battlefield, were civil enough to share one of their greatest assets: Giovanni Paisiello.

Jacques-Louis David, “The Coronation of Napoleon”

I find it one of the most colorful twists of music history. Paisiello, a composer largely forgotten today, seemingly held several top positions in the music world—and grew tired of them. Extremely powerful men negotiated over his services. All while the brilliant and beloved Mozart couldn’t land a single maestro position in a respectable European court.

At least Paisiello had the flair and tenacity to engage the great leaders of the world, yet still do it his own way.

copyright 2017 Teddy Niedermaier

no reproduction or reuse without permission